Comics have never been more popular among children and adults alike. At QinPrinting, we collaborate with independent comic creators every day. Here are five great tips to help you make your comic stand out from the crowd.

We love collaborating with comic book creators. It’s always deeply satisfying to see a new comic evolve and play our part in producing a beautiful printed edition which does justice to the ingenuity and creativity of our clients. Now, several of our customers are old hands with a thriving self-publishing business already established; others are just starting out with their very first comic. If that’s you, then we’ve got a handful of our most helpful tips to make sure that your comic stands out from the crowd.

All these ideas come from years of experience and comic book collaborations, so while many may seem simple, they’re high-value and worth considering as you embark on your own comic creation journey. We’ll assume that you’ve already come up with a story idea, developed a theme, and decided on your main character. So, let’s dive into our top tips for drawing your comic — although many of these can apply to the writing and dialogue side, too.

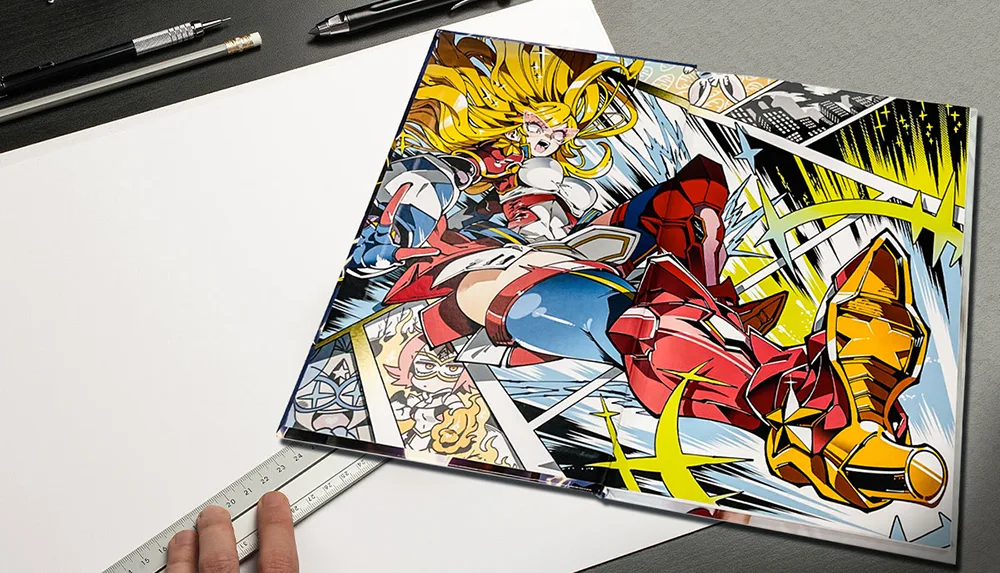

1. Add unique visual traits

In the world of mainstream literature, TV, and the movies, key characters often have a catchphrase, an object they always carry, or a behavioral habit they always show. Famous catchphrases of comic book heroes include, for example:

- “Avengers assemble!” — Captain America

- “Cowabunga” — Michelangelo from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

- “I am the law!” — Judge Dredd

- “Holy smoke, Batman!” — Robin

- “It’s clobberin’ time!” — The Thing

Items and clothing — other than the spandex outfits and capes! — that come to mind, could be:

- Wonder Woman’s Lasso of Truth

- Captain America’s Shield

- Thor’s hammer

- Indiana Jones’s whip

And behaviors that are instantly recognizable:

- Wonder Woman’s crossed forearms

- Superman’s flight posture, with one clenched fist drawn to his chest and the other stretched out in front

- Any number of special stances, gestures, and behaviors, such as the Joker’s insane laughter and Batman’s “power stance” with legs astride and arms folded

These things are there for a purpose. They make the main character or characters immediately recognizable. They make them stand out. You can do the same in your comic to help distinguish your protagonist and other important characters.

But as you have an exciting visual dimension to your work which is in the drawing, you have extra tricks up your sleeve that go beyond catchphrases, clothing and objects, and mannerisms. For example, you give them certain colors that don’t appear anywhere else in the frames. They could have a stream of glittering stars that swosh behind them as they move. What about a distinctive body-shape or extra limbs? Anything goes in the crazy world of your imagination!

Pro tip: your main characters should be instantly recognizable from their shadows or outline alone.

2. Capture the language of color

Color is part of the emotional and atmospheric language of comics. In other words, people, objects, and places needn’t be given their natural colors. You should use color to express character, mood, and meaning.

It’s also an excellent way to quickly orient the reader as they move through different scenes and locations in the course of the story. The sickly green glow of Dr. Death’s laboratory, for example, the blue wash that colors the city streets in the early dawn, and the limpid yellow light of a summer meadow. If you choose specific color schemes for particular locations, then you can quickly indicate to the reader where they are without having to “pan out” every time to show the whole lab, or cave, or apartment, or spaceship, or wherever.

Color is a great way of suggesting time, and the passage of time. So, brighter, more vivid colors for a summer day, more subdued grays and blues for dawn or dusk, and deep purple shadows for night. These are just suggestions so you get the idea. Your choice of colors and what they mean is down to you and your creativity. You can certainly break the standard rules if you think it will improve your comic. But always be consistent to avoid confusing your readers.

Pro tip: give your key locations distinct color treatments to quickly orient your readers to changes of location without breaking the pace and flow of the story.

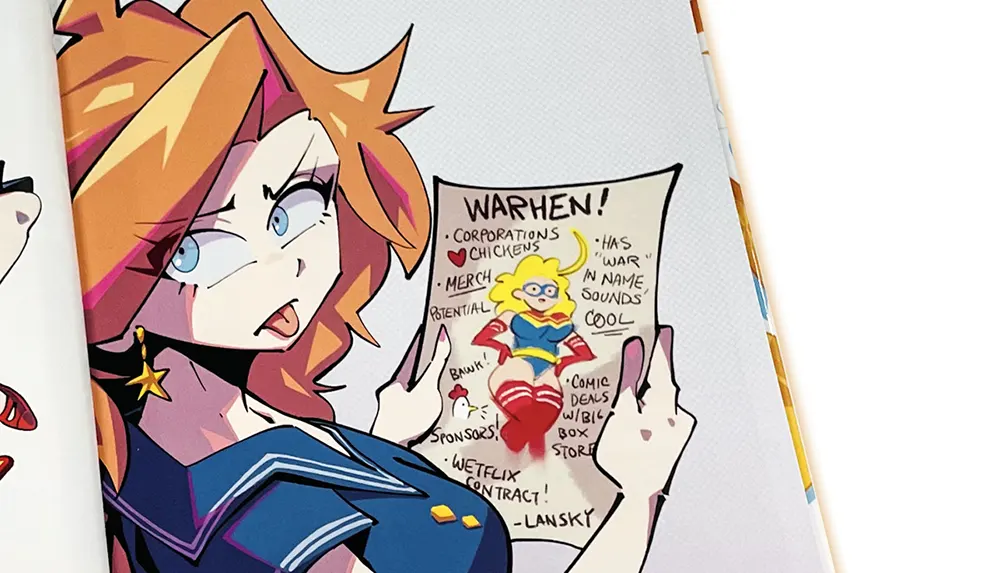

3. Work out where the words should go and what they look like

While there’s no doubt that the artwork is the fundamental, non-negotiable element of any comic book, most also have at least some text. But there’s a golden rule in professional comic creator circles, and that’s to make sure that text only shows what a picture can’t; a radical shift in time or location, or the inner thoughts of a character, or a necessary “deus ex machina” commentary, for example. So, comic book text falls into three categories:

- Dialogue—expressed in “speech bubbles”

- Narration—usually confined to a rectangle in one corner of the frame

- Interior monologues—in “thought bubbles” like speech bubbles, but connected to the character by a string of smaller bubbles rather than the standard “pointed tail”

Now, to make your comic stand out, you can work with the visual dynamics of the text. This encompasses three factors: text placement, text style, and bubble or box style.

- Text placement —where the speech, narration, or monologue goes within the frame

- Text style—which font? Or will it be “art text” (like POW!) or will certain words be bolded, italicized, or otherwise changed for emphasis?

- Bubble and box design—speech bubbles, thought bubbles, and narrative boxes can be a variety of different shapes and sizes to help express the emotion or impact of the words

A common rookie error when making your first comic is to concentrate on the artwork to the exclusion of the text—and then find that you’re having difficulting “cramming” the speech and narration into spaces not designed for them. So, think of the text as part of the artwork, not something added afterward. When drawing your “roughs”—early stage outline which block out spaces with very little detail—incorporate your speech and thought bubbles, and your narration or commentary areas, into the visual design right from the start.

Pro tip: try positioning speech and thought bubbles in the top and bottom corners of the frame so that they don’t interfere with the reader’s view of the action, and make the tails point to the speaker’s mouth.

4. Cliffhangers and rhythm

In the old-style “pulp fiction” of the 1950s—a close cousin of the modern comic—almost every chapter ended on what’s known as a “cliffhanger”. A cliffhanger is an exciting moment which occurs at the end of a chapter but is unresolved, making the reader turn the page and start the next chapter to find out what happens next. It comes from the classic scene in which the hero falls or is pushed off the edge of a cliff but is able to hang on to the edge, or a tree root, as they dangle over the thousand-foot drop into the raging sea or the volcano’s boiling mouth, or the pit of snakes and crocodiles, or whatever terrible threat the author has conjured for them to face. Of course, not all cliffhangers need be so dramatic. If every page of your comic ended with such high octane peril, the reader would soon experience overload. As a page ending, rather than a chapter ending, you could go for other options as in the following examples:

- A simple question asked by a character but not answered until the following page.

- Or someone shouts, “Look out, behind you!” and the last picture on the page is the heroine spinning around with a look of shock on her face, forcing the reader to turn the page to find out what has caused her reaction.

- How about a character who has received a mysterious package—which the reader knows is a bomb—and in the last image on the page, the character decides to open it.

Those are just three possibilities, but you get the idea. You can treat what happens on the next page in several ways. So, following our examples above:

- In example one, another character could simply answer the question; or the protagonist who asked the question could witness something happening which either answers the first question or raises a new one; or perhaps, just as the answer is about to come, there’s a dramatic interruption and the reader must keep reading to figure out what the answer is and what will happen next, or…

- In example two, on the next page we could see whatever it is—a monster, the gangsters, something about to fall on her, etc; or you could continue the suspense with the creeping shadow of whatever it is getting ever closer over the next few frames; or maybe it’s a false alarm—just a spider, say, which the other character has a phobia about,or a looming shadow which turns out to belong to a mouse, or…

- In the third example, the bomb could explode; or the character could realize what it is and throw themselves behind the sofa just in time; or maybe you led the reader to think that this was the package with the bomb in it, but actually it’s something else, or…

So, this is a great way to keep the reader gripped and turning the pages of your comic book. An important thing to remember is that not every page should be a cliffhanger, and those that are can and should vary in intensity to keep the rhythm of the story interesting. The biggest impact surprises should occur at about the end of the first quarter of your story, the middle, and the third quarter before the final scenes play out to the end.

Pro tip: for your ‘big scene’ cliffhangers, consider using a “splash page” to follow up. A splash page is an image that fills a full or half page and is used to add surprise and create maximum dramatic impact.

5. Planning, patience, perseverance, and starting over

There are so many elements to comic book creation that it can all get complicated and even frustrating at times if you make a major mistake and need to start over. That’s a great advantage to using digital drawing software; that you can save your progression in steps, make instant copies and variations, and step backwards and forwards through your process. If you’re using traditional drawing materials and techniques—as many professionals do—try to work in phases, getting the main areas “blocked out” at the storyboard stage, make sure the narration and dialogue will fit their assigned spaces, and keep notes about colors and characters to make sure you’re consistent. To the comic book creator who prefers traditional methods, architect-tracing paper, the scanner, and the rough draft are great friends.

But whichever technique you choose, you will make mistakes. So, build that expectation into your process from the start. The key to a successful comic is careful planning coupled with persistence and a willingness to go back and redo something if it’s not working. See each error as an opportunity. Dive deep into the process, and enjoy it!

Pro tip: never throw anything away or delete your previous iterations. You never know when something you did might be useful in the future. The more material and choices you have to work with, the better your chances of hitting on a solution when you come up against a problem.

Talk to us!

Whether you’re in the early stages of planning your first comic book or you’re preparing your completed files ready for printing, we’re always happy to hear about your project, either to chat through how we can help you realize your comic book or to give you a personalized quote on professional-quality printing. Get in touch. We can’t wait to be part of your next comic book adventure!