Self-publishing children's books may be more of a challenge than writing for adults, but with the right approach, you can make it succeed

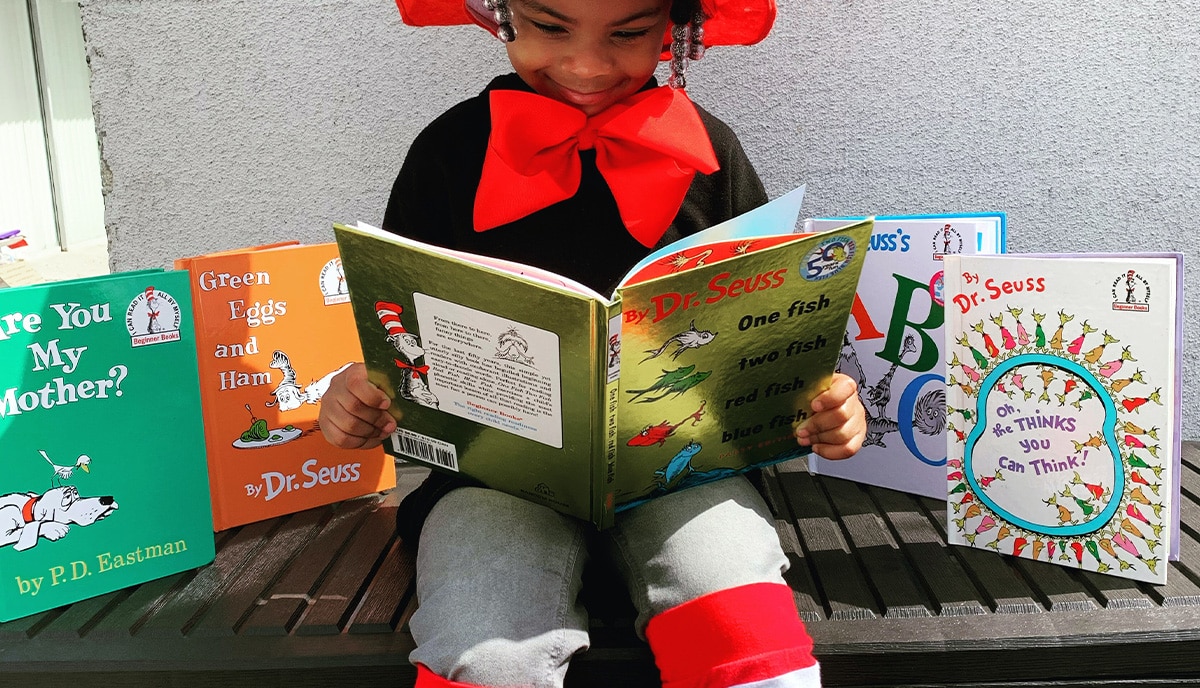

Photo by Catherine Hammond on Unsplash

Why write for children?

The first and most important thing you need to examine before you decide to write and publish books for children, is your motive. If you haven’t already asked yourself why you want to write for children, then do so now before you go another step along the road. You know, there are right and wrong motives, and you need to make sure yours are right.

If they’re wrong, you’ll be wasting all your time and effort and throwing money away when you self-publish. Get them right, and whether you’re ultimately successful or not — and that depends on how you measure success — you will at least have given yourself the best chance of writing a good children’s book. Let’s unpack all this now.

The wrong reasons to write for children

Before we go into the best motives to write for children— the motives that will sustain you through the arduous and challenging process of planning, writing, editing, self-publishing, and marketing your books — let’s first expose the wrong motives. Please note, these are not morally wrong: they’re just motives which won’t work. They’re wrong in the sense of misguided or ill-thought. So, don’t feel bad, or judged, if you recognize these in yourself. That’s a great first step! You can then go on to replace them with the good motives that we’ll get to in just a moment.

Your own children love to listen to you tell stories

If you have children and you read them stories — or make stories up and tell them — that’s a beautiful thing and you’re giving your kids a treasure beyond dreams: the gift of your loving attention; of the delight and possibilities of imagination; of language, communication, literacy, and understanding. But recognizing that you’re a good oral storyteller — or a good narrator of other people’s stories — isn’t necessarily the best motive for trying to write your own stories for children.

Especially if they’re your own children doing the listening. Your children know you and love you; they want your attention as a gift in itself — quite aside from the form and content of the story you’re reading or telling — and they share your genes and your culture. You’ve chosen the story for them as individuals, so it’s likely a good fit. When you write for children generally, that’s not your audience.

As a children’s writer, your readers will be children you don’t know, from parents and families you’ve never met, from all walks of life, and from a range of experiences and expectations you cannot even guess at. So, you can’t really write for those children. And writing for your own will be too directed by your knowledge of them; it will be too specific; too exclusive.

So, wait a minute! If writing for your own children won’t cut the mustard and writing for other people’s children is impossible… who’s left? For whom are you supposed to write as a children’s author? We’ll answer that in just a moment. But first, let’s look at the other wrong motive.

You're not a good enough writer to write for adults

Let’s be super-clear here: writing for children is not easier than writing for adults. Anyone who thinks so will be the worst kind of children’s writer: simplistic, condescending, and out-of-touch. In fact, it’s commonly accepted in the writing community that writing for children is harder than writing for adults.

Adult audiences are far less challenging and have fewer needs. They’re adults after all; so, they’re a little jaded, less curious and inquiring in their minds, far less critical. Children, on the other hand, are alert, awake to every nuance and contradiction; they apply a severe logical criticism to every experience; they always want to know why, their thirst for new knowledge and reasoning is insatiable; and the thirst of their febrile imaginations is not easily slated with clichés or half-baked metaphors.

While an adult may listen politely to your dreary discourse or persevere through your pedestrian prose to find out how the story ends, a child will lose interest, fidget, and run off to play if you do not capture and hold their attention. To write well for children is to stretch your creative powers to their limits. It’s to offer them your best work; to push and challenge yourself at every step. Good children’s writers are the best in the world. Nothing else will do.

So, if your motivation to write for children is because you think it will be easier than writing for adults, forget about it. Go do something else. Seriously. Because to write well for children is to accept the toughest — but if you can do it, most rewarding — literary challenge that it’s possible to attempt.

The only good reason to write for children

So, what does it take to be a good children’s writer? It takes everything that you need to be a good writer of any sort: an excellent command of the language and a wide vocabulary; a lively and original imagination; a deeply questioning and curious mind; the habit of paying close attention to the world around you; a nose for a good story; an uncommon insight into human nature; and an astonishing supply of creative energy and mental discipline.

But it also requires something else: the added ingredient that makes a good children’s writer. That is, a profound understanding of the reality of children’s experience; sympathy and empathy with the state of childhood in abundant and equal measure; a deep and lively connection to your own inner child.

The only good reason to write for children — the only motive that will work — is an ardent and unquenchable desire to communicate with the child you remember in yourself; to entertain, to reassure, to enliven, to answer, to satisfy that yearning inner child. The child who still lives within you and urgently wants to play; the one who obstinately requires answers; that mischievous, cunning, innocent, daring, terrified, rebellious, steadfast, brave, infinitely curious and tenderly fragile child whose eyes are wide with wonder at even the most banal details of the world.

If you can write for that child — and do so with honesty, precision, and grace — you can write for all children.

Getting started: what to do before you write

Read, read, read

If you’ve never written a book before — or have never written anything for the juvenile market — the first thing you must do is research. What does that mean? It means that you need to read as many books as you can get your hands on. The books you read can include some of your old favorites from your childhood, but you’ll also need to branch out and read more contemporary works, too. Language, tastes, and story treatments change over time and while there’s no need to imitate a style with which you’re uncomfortable, you need to get a feel for what’s being published today.

Also, read widely across age groups and genres. So, consume novels for early teens along with Middle Grade chapter books for those just starting to read alone; throw illustrated books for younger readers into the mix; and don’t forget children’s board books for toddlers and infants. Read as much and as widely as you can.

Oblige yourself to read in genres that you might not normally explore. So, include in your reading list at least some science fiction, fantasy, mystery, historical, school, contemporary, romance, adventure, and anything and everything else. If you’re not already a fan of children’s literature, then you may be surprised by the range of story-landscapes that this rich and fertile imaginative literary geography covers. Explore it.

But don’t just read. Take notes. Whether you make notes with a pen and paper, on an app on your smartphone, with a voice recorder, or in some other way doesn’t matter. What matters is that you keep a record of all your thoughts, impressions, ideas, and responses to every book you read.

As you go through this process, you’ll begin to form a clear idea about what you like and don’t like in children’s literature. Your reading will spark ideas for your own stories, characters, plot lines, and situations. While you must avoid plagiarism (copying another writer’s ideas) there’s no harm in seeking inspiration. All good writers are inspired by other writers. As Isaac Newton, the famed 17th century physicist and parliamentarian, said, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Whatever you like and don’t, if you wish to write children’s literature, then you must read it and enjoy it. You must discover those authors, and those characters, and those stories, which inspire and delight your inner child. If you discover that you don’t like children’s books, then you won’t be able to write them.

If you wanted to learn to play the violin, you would surely expect to listen to and enjoy violin music, wouldn’t you? If you wanted to be a movie director or a screenwriter, you could hardly think of doing so if you hated going to the movies. And if you wanted to be a painter but just couldn’t be bothered to go to art galleries and exhibitions, what chance do you think you would have? In the same way, if you want to write, you must read; and if you want to write for kids, then you must read kids’ books.

Dream and ponder

You will occasionally hear of writers who claim that stories and characters pop into their imaginations fully formed and ready to go; and that they don’t plan or write an outline first, they just start writing and don’t stop until they’re done. It may be true. But if it is, it’s very rare indeed. In most cases, you will need time to dream up several ideas, mull them over, roll them around in your mind, and generally take time to discover the idea which keeps you up at night with excitement.

The seed of the idea might come from something you’ve read — not necessarily a children’s book — or maybe an encounter with a person or situation that strikes you; a memory; a piece of music; a building or place; or something more abstract altogether like an atmosphere, feeling, or the ghost of an image you can’t quite pin down. But when you have it, you’ll know it. It will feel like destiny, or falling in love, or anticipating a long-awaited reunion.

But the seed or ghost of an idea is only a starting point. You’ll need to coax it out into the light of your conscious mind, and nurture it into a more definite form. The best way— possibly the only way — to do that is to decide on a character, a protagonist, a person whose story this will be. Once you get to know the who of your story — whether that’s ‘the little red ball’, a young kitchen hand at King Arthur’s court, a brave, talented princess, a rebellious teen rocker vampire, a talking dog, a shy boy ballerina, or anyone else at all — then the where, what, when, and why will all begin to emerge. But the best stories start with a person, and so should you.

Research

The next stage before you actually begin to write your children’s book, is to research. What kind of research and how much you must do depends on how much knowledge and experience you have as a writer on one hand; and on the other, how familiar you are with your subject and setting.

So, if you’ve never studied creative writing — either formally or informally — and know nothing about the principles of story structure, character development, emotional arcs, dramatic conflict, irony, voice, point of view, narrative distance, and all the rest, you’ll need to spend some time educating yourself. You’ll learn a lot by reading the kind of stories you want to write. But you can back that up — and speed the process — by reading a healthy handful of good writing instruction books, blogs and vlogs, and listening to and watching podcasts, attending talks and discussions, and possibly taking a course in creative writing.

Once you’re familiar with what writing means at the technical level of the craft, you’ll be ready to try doing it. But you may still need to do further research to support your story. If you’ve chosen a young lady in Renaissance Italy, for example, as your heroine, you’ll need to get enough information about the historical background — the way people lived, worked, dressed and so on — to be able to write convincingly in that period. Likewise, if your story is set in a modern high school in Chicago or Boston and you’ve never been to either of those places, you’ll need to do a little research before you get started.

Research could be needed even when writing for younger children. In short, any fact of which you’re not sure must be checked and made right. The only exception would be a completely invented fantasy world; or that story about ‘the little red ball’ whose world and adventures may be simple enough that you can get away with just making it all up!

Plan your story

The last stage before knuckling down to the tough business of writing your story from the first line to the last, is to make a plan. Again, you’ll read about authors who claim they do not plan. They just sit down, start typing, and the story “writes itself.” Once more, that may be true in some very rare cases, but you’ll save yourself a deal of struggle, hard work, and confusion if you assume that you are not that kind of writer — at least until proven otherwise.

How you plan and in how much detail is up to you. These things vary from writer to writer and you will discover what works best for you by trial and error. Your plan could be as simple as a one-page synopsis with a paragraph outlining the key events in each of the “three acts” through to a multi-page document with every detail of the inner and outer progression of the story mapped out step-by-step.

Whatever kind of plan you choose, it will help you get started with confidence, give you chance to figure out your story before you waste words on something that doesn’t work, and keep you on track when the going gets tough — as it certainly will. But don’t get hung up about it. At this stage, there’s no-one watching but you. And it’s your plan and you have every right to diverge from it, change it, or ditch it altogether and write another one as you get started and discover which way your story wants to go.

Write the first draft

Writing — and completing — the first draft is one of the most exciting and challenging tasks facing any author. The phases you’ll go through and the obstacles you must overcome to get from the beginning of your story, through the middle, and drive on to the end, are the same for a children’s writer as they are for an author writing for adults. Let’s look at how to write a first draft.

The most important thing to remember here is that you don’t need to get everything perfect the first time. All good writing is rewriting. Think of any book by any author — however famous — that you’ve enjoyed. The first draft of that book was almost certainly messy, full of plot holes, poor phrasing, and all sorts of other stuff that didn’t make the final edit. Of course. The process of writing well is iterative. It always was and it always will be, for every author ever until the end of time.

So, when you’re writing the first draft, relax. Enjoy it. Experiment. You’ve got your plan as a starting point and a rough ongoing guide, so just dive in and keep going until you get to the end. The result will not be very good. It will be a crappy manuscript. But it will be a complete crappy manuscript. And that is worth more than just three polished chapters of an otherwise incomplete story. Three standalone chapters on their own are worth nothing. A complete manuscript — no matter how poor — is worth its weight in gold; it’s something you can work on.

And once you have that first draft in the bag, the work really begins. The most important aspect of writing is editing. That’s where the alchemy happens. That’s where the dull, base metal of your first draft is slowly, incrementally, sometimes painfully, transformed into the magical gold of a publishable manuscript.

Edit your manuscript

Once you have your first draft in hand, take a break to celebrate. It’s a good idea to leave your work unread for a few days or weeks before you come back to it to begin the lengthy process of several rounds of editing. That way, you allow yourself a period of well-deserved rest before getting stuck in to the next stage; and you can also step back and get a bit of emotional distance from the story, as you’ll need to engage your more critical faculties for editing.

While you may want to do the very first round of editing alone — and that’s fine — you should engage a professional, experienced editor to work on the manuscript as soon as possible. Few writers attempt their own editorial critiques. It’s just impossible to see the work with an objective eye.

Professional editors — many of whom have years of experience with the big publishing houses and literary agents even if they offer their services independently — also have a profound knowledge of story structure, characterization, plotting and other factors that will make a book sell when they’re done right and will cause it to nose dive if not. That’s understanding and information you probably don’t have — yet — and could make all the difference between success and failure. Don’t be afraid of editors! A good one will be your best literary buddy.

Typically, there are three levels of editing you’ll need to do. They may each be done by an editor who specializes in that aspect or a single editor may do it all. The three levels are:

- Developmental editing

- Copy editing or line editing

- Proofreading

The developmental edit takes a broad view of the aspects of your story, plot, and characters to identify anything that isn’t working and may need fixing. A developmental editor will read your full manuscript — perhaps several times — and deliver a report detailing what they think works and where there’s room for improvement. They’ll consider plot, character arcs, pacing, theme, and more. You may then go through several further rewrites while you fix all these ‘big picture’ issues.

Once the story, plot, pacing, and character arcs are all solid and well executed, it’s time to drill down into more detail. This is where the copy edits, or line edit, comes in. A line editor goes through your manuscript — as the name suggests — line by line. They’ll make suggestions about language, vocabulary choices, images, metaphors, sentence length and structure, dialogue, rhythm, and pacing. The line editor’s key occupation is to help you to improve your style, diction, and overall quality of writing.

After the line edit — which again could give you several rounds of rewrites to do before you agree that everything is ‘just right’ — it’s time for the proofread. A professional proof-reader has a comprehensive understanding of grammar, syntax, diction, spelling, punctuation, and — most importantly — an eye for detail that could only be exceeded in acuity by an eagle owl!

You should now have a good story well told in grammatically correct and stylish prose with perfect spelling and punctuation. In other words, a finished book — with backup copies saved on your hard drive, an external drive, and in the Cloud, please! You’re almost ready to go to press. Why almost? Because between the printed-out manuscript sitting on your desk and the inky rollers of the printing press there’s a little more road to travel. The milestones on this section of the road are design, formatting, and layout. So, we’ll look at these now.

Design, layout, and format for a children's book

Before you can transform your manuscript from a wad of foolscap into a book for sale, you’ll need to engage an artist and designer — who may or may not be the same person — to create the artwork and cover layout for your book and format the interior pages, including the titles, paragraphing, pagination, dividers, title page, copyright page, acknowledgements, and back pages. The designer must also prepare the files they make for the printing press so that they are “print-ready”.

You’ll need to buy an ISBN and a barcode to print on your book, too, and register it — so that stores and libraries can recognize it and get information about it for themselves and customers. These are available from Bowker in the US and Neilsen in the UK.

It’s a good idea to talk to your printer at this stage. A reputable and competent printer — hello, that’s us, by the way! — can do more than just print your books. For example, we can liaise with your designer to provide all the technical information — such as dimensions, paper weights, trim sizes, bleed margins, color spaces, and more — that they’ll need to prepare the files for the press. We’ll discuss with you the choices you wish to make about bindings and other important matters. And then we’ll then check everything manually to make sure that it’s all in order before we load the paper and set the machines rolling.

If you wish, we also have our own in-house designers who can work with you to get the book you want based on the artwork and ideas you provide. While you’ll need to get an outside designer to create the files, we’ll work closely with them to make sure everything’s perfect. We have a lot of experience with this and whether it’s a fancy hardback edition with a glossy cover, gold foil stamping and an embossed title, a trade paperback, a board book, or a specialist book such as a ‘pop-up’, we can guide you step-by-step through the process to make sure that you’re completely happy with the finished project.

How to sell self-published children's books

Once you’ve written, designed, and printed your book; then what? Strictly speaking, until it’s out there in the world available for people to buy and read, it isn’t published yet. As a self-published children’s author, how do you promote and distribute your book? Before you can make a marketing and promotion plan — which you will need to do — it’s important to understand who your buyers are. Because, when it comes to children’s books — unless your book is in the older age-range, say teens and young adults — it’s not the kids who choose and buy the books.

Your marketing and promotional efforts must be targeted to parents, guardians, teachers, and librarians. These are the ‘gatekeepers’ who select books to buy for children. They’re the people with the buying power and so it’s actually to them that you need to sell your self-published book.

You can distribute and sell in the broad market, of course, by signing up with Amazon, Ingram, Bowker, Nielsen, and other distributors. This can be a complex process, but just follow the instructions each gives you and make full use of their mostly excellent client services. Amazon is perhaps the most limited option for you as they focus on literature for young adults and up, unless your book is published by a mainstream publishing house and they’ve put a significant amount of marketing effort behind it. The advantages of getting your book distributed with the others is the chance to get into the catalogs from which high street books stores and libraries choose their stock.

But as a self-published writer of children’s books, you’ll need to do quite a lot of leg work. Still— while it’s tiring and there’s a learning curve if you’ve never done anything like this before — it can be a lot of fun and hugely rewarding in many ways over-and-above just selling your book. Let’s look at a few of the best tried-and-tested ideas to get you started.

Organize school visits

Get in touch with schools. In the first instance, a quick phone call to briefly introduce yourself and find out who you should talk to about a visit may be helpful. Follow that up with either an email and/or a visit in person. You should be ready to tailor your offering to the school’s needs at that time, but essentially, make sure that you’ve prepared:

- a workshop you could run with classes in the age group for whom your book is written — these could be writing workshops, thematic workshops, and question-and-answer sessions about how you wrote the book or to discuss the story itself

- give a talk or presentation to the school assembly

- with older children, give a reading of the first chapter of your book or selected passages, and then moderate an open forum discussion about the characters, themes, and issues in your book

- offer an interview to the children in a class who can then do a write up for the school journal

Getting into schools is a great opportunity — or, rather, hundreds of opportunities — to promote your book directly to your readers and to those who are responsible for their education. You will need to do a lot of preparation and research to find out all the details of how and what to do to run a successful workshop, discussion, assembly, or other event in school, but the rewards are worth the investment.

Of course, you can feel confident about asking the school librarian to stock a few copies of your book in advance of your visit and you should get permission to have your books on sale, too; especially useful if you run your event as an extracurricular activity and parents can come in at the end to pick their kids up.

If you don’t have either the time, skills, or confidence to organize a school tour yourself, a quick Google search will turn up hundreds of agencies who specialize in author tours and promotions. Just bear in mind that going that route can be expensive and may not give you a good return on your investment. So, check out all the options carefully before you commit.

Do a library tour

Doing a library tour is another great option and more-or-less needs the same offers and skills as one for schools. You should normally contact the county librarian and take it from there; but any of the staff in your local library will be happy to help, at least to point you in the right direction. Likewise, if you’re not confident or don’t have the time, an agency may be able to help with this, too.

Another advantage of the library tour is that it’s a great way to get your books into libraries! And unlike schools, it’s an opportunity to run events for parents, too. You could do a short course on ‘how to write a children’s book’ or a talk on ‘the future of children’s literature in America’; or just an introduction to your book with a reading and Q&A, especially if the book touches on themes and issues that concern parents, too.

Do a blog, vlog, and podcast tour

Another great option to throw into your children’s book marketing mix is a tour of blogs and vlogs (a video blog) dedicated to children’s literature, education, development, and other issues. There are more of these than it’s possible to count, probably. But a Google and YouTube search should quickly help you put together a list of possible venues to approach.

Many blogs, vlogs, and podcasts which are open to guest posts, interviews, Q&As and other opportunities say so up front. Others may have a more discreet link you’ll need to hunt down, while others may need you to email the owner and ask. It can be quite a long haul and you may need to send a large number of queries to build up a reasonable list of positive responses. But there are several reasons why it may be worthwhile.

In the first place, several of the best-known blogs, vlogs, and podcasts have millions of readers, viewers, and listeners. That’s a lot of out-reach. It would be worth putting in some work to achieve it.

Secondly, unlike, say, a newspaper press release which is published and gone within 24 hours, the content you create online will get a lot of upfront exposure. It could sit on the front page for at least a few days and possibly weeks and months. And after that, it’s still there in the archive for people to find years down the line.

And thirdly, top bloggers, vloggers, and pod-casters have built up powerful trust-based relationships with their communities. In other words, their audiences are responsive and so aside from building your brand and reputation, you can expect a good chunk of direct sales from the right exposure on the best venues.

Social media

Let’s not mislead you. Running an effective social media marketing campaign for a children’s book — or anything else, for that matter! — is a lot of hard work and definitely not a ‘quick-fix’ solution. Social media is all about building relationships. And those relationships must be genuine. It takes time and much effort. You can’t just slap up a picture of your book and expect people you don’t know to rush out to buy it. It ain’t gonna happen.

But if you already enjoy social media — and you’re prepared to learn how to use it effectively as a slow-burn, long-term marketing strategy, then it’s an option worth exploring. Whether you handle your social media accounts personally or outsource the ‘leg-work’ to a third-party social media manager is a tough decision and one that only you can make. As a children’s author, it may be best to at least start out keeping it hands-on and personal.

And remember that on social media — authors, teachers, librarians, and other bookish types tend to favor Twitter — you’re not targeting the children directly. So, you need to make sure that your posts appeal to, and offer value to, the guardians and gatekeepers who actually buy the books. While it seems easy, social media is still a hard nut to crack from a marketing perspective. If you don’t have a lot of energy for it — and, above all, enjoy making contacts, chatting, reading, and sharing on the socials — then it may not be for you.

Your own website and blog

Most authors choose to set up their own website and blog. Again, a quick Google search will present you with a multitude of options for how to set things up, what to write, and so on. It’s possible to set up a perfectly serviceable website and blog for free.

Following on, there’s a range of paid options which can offer you features you may want down the line. For example, your own e-shop, a personalized domain name, and more. But one of the free options from WordPress, Squarespace, or Wix — to name just a few — should be fine to get you started.

Becoming a blogger is a long journey — but for a writer, very often an enjoyable and rewarding one — and there are no shortcuts. Our only advice would be to try out the free options while you get started, test the waters, and figure out if it’s right for you. The Internet is littered with ‘dead’ blogs that people enthusiastically started and then — realizing just how much work was involved — let slide. So, keep your dollars in your wallet until you’re sure that you’ll be able to sustain it.

Other options for marketing your self-published children's book

That’s by no means an exhaustive list. You can try press releases, radio and TV appearances, paid advertising, book fairs, trade fairs, and more. But the options we’ve listed here are popular, open to anyone to start from home, and needn’t cost anything other than imagination, communication skills, and determination. And once you’ve written a book, you’ll have proved that you have those.

That pretty much wraps up our guide to taking your first steps in self-publishing children’s books. We won’t pretend it’s easy. But with a clear-headed approach and hard work, there’s no reason you shouldn’t join the many other children’s writers who’ve taken this route and made a great success of it.

Don't forget the book!

Of course, between finishing your final draft of the story and setting out on your marketing journey, you’ll need to get a beautiful, custom printed batch of books made ready to sell. So, as soon as you’re near the complete draft, get in touch. We have decades of experience helping self-publishing children’s authors create and print the most beautiful edition of their book possible, while keeping costs down. If your book and designs are already complete, use our free quote engine to help you calculate the cost of producing your book. If you’re not quite there yet and have questions, talk to us. We’re an expert, friendly team. We’d be happy to help!