We guide you through the essential steps to take your basic board game design and develop it into a robust and satisfying experience for players

Board game design is an iterative process that cycles through several rounds of ideation, creation, implementation, testing, and evaluation. Getting your basic design together is only the first step. Next comes development. In the industry, it’s often the case that game designers don’t get involved in development. Designers and developers can be two distinct species in the game creation ecology. But if you’re a beginner or an independent game creator, then you will probably need to follow through on both closely related activities when responding to the challenge of how to develop a board game idea.

Each developer has their own approach to these things. So, we recommend you go to conventions, read blogs, check out the subreddits and anywhere else that game developers meet and share their ideas and experience. Don’t be shy about talking to other game designers and developers. It’s a friendly and supportive community which thrives on a sense of collaboration and mutual help. Most developers will be happy to guide and advise newcomers.

So, in this post, we’ll explore the core concepts of board game design and development according to our almost 30 years of experience printing and manufacturing games for the industry and for independent creatives and self-publishers. Our aim is to give you valuable insights and techniques to focus on and apply your creativity to generate solid, enjoyable, and memorable gaming experiences for players. Whether you are a seasoned designer or a novice looking to embark on a board game design, we’ve packed this post with resources and tips to help you advance your game design and development journey.

Communication is the key

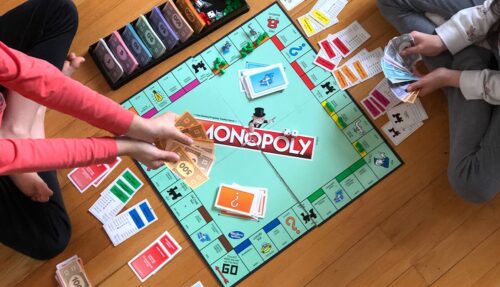

The essence of all board games is the fundamental concept of communication. Think about it. Without communication, no game could work. Passing the turn from one player to the next, sharing and following the rules, interacting via the game components, agreeing to accept the win conditions, the laughter, concentration, and “communion” that the gameplay experience is about are all forms and expressions of communication.

So, as a game developer, make sure you hold this core reality at the forefront of your mind in everything that follows. A good game is one in which all these channels of communication interrelate and interact smoothly to carry the gameplay experience forward. When a game fails, it’s almost always because of a broken link in the communication chain.

The core premise

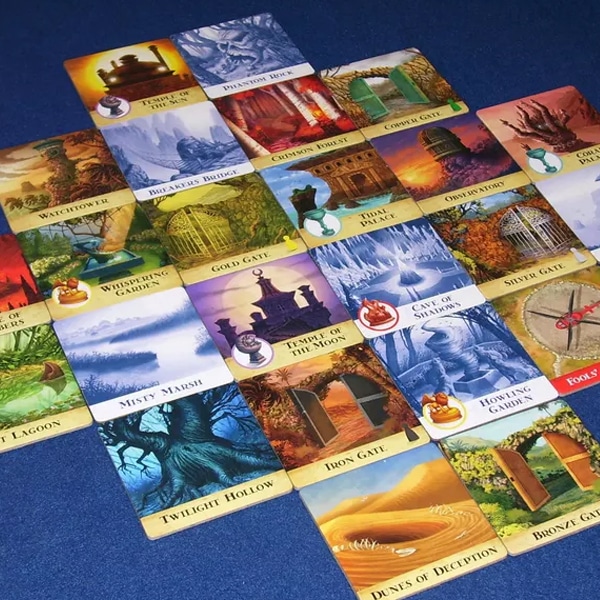

If the core premise of your game design is faulty, nothing that you build on or around it is likely to work. So, the basic premise of the game — which is the most stripped down functional element, the essential idea which drives the mechanics, justifies the components, provides a win condition, and makes sense of the rules — is the first place to look, to test, to get right as you begin the game development process. To make this clearer, let’s analyze a few popular board games and identify the core premise they’re based on.

Forbidden Island: The core premise of this game is to escape with the treasure before the island floods. Every other aspect of this game’s design has been developed to support and respond to this essential aim of the game: a race against time. The character roles, the flipping tile mechanics, the components, the rules, and the win condition all stem from this premise.

Small World: The core premise of Small World is territory occupation. The idea is to gain control of the largest chunks of ground. So, everything about this game — the tile placement mechanic, encircling, and the points system, all arise organically from the soil of this primary principle.

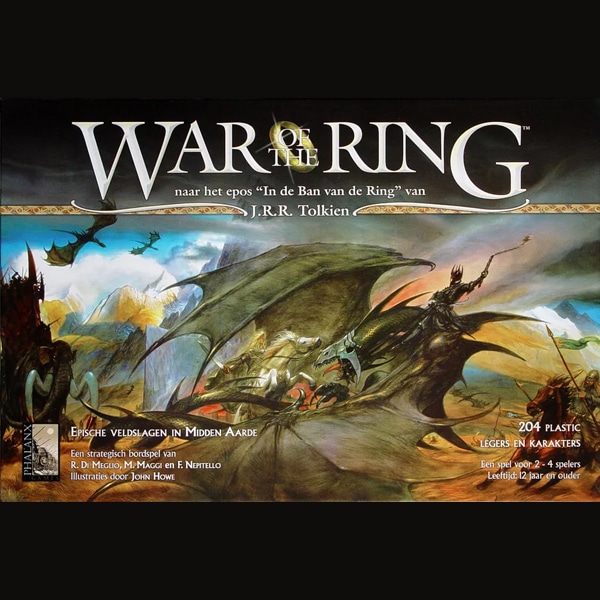

War of the Ring: The core premise of this game, based on Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings novels, relies on area control as players try to win the war through strategic and tactical maneuvers. While it’s an area control game, the premise is more related to the strategic elements and that shows in the mechanics, layout, components, and rules.

Chess: This classic game has “capture the king” as its premise. Simple as that — but what a challenging, complex, abstract strategy game it is! An evolving spatial puzzle, the movement mechanics of each piece, the chequered board, and the rules for when the king is captured (checkmate) all refer to the premise.

Whether you’re developing your own game design or you’re working on someone else’s, it is a vital first step to identify and define the core premise of the game. To do this, strip away each element layer by layer: so, what if the board was just squares (without the scenery printed on, say) and the player pieces just colored discs (rather than, perhaps, custom miniatures); what if each player could only make one action per turn (instead of, maybe, three) and so on. Strip it away until the last step before it breaks. Then ask yourself, “Okay, so what is this game about once it’s reduced to its essential elements and nothing more?” That’s your core premise.

How to fix a broken premise or strengthen a good one

As we’ve pointed out at the start, often if there’s something that’s not working in your game, whatever it is, it’s because the premise isn’t right or that it’s a good premise but the mechanics or components, rules, or win condition have been “bolted on” for some other reason—the aesthetic proclivities of the designer, for example, or simply ill-thought out—rather than growing organically as logical consequences of the premise. With board game development, if you get the premise right, everything else should fall naturally into place. So, what can you do if you have a broken premise or a good one but the game’s still not working? Here are a few ideas to get you thinking and experimenting along the right lines.

- Brainstorm: Clear the decks and start again by brainstorming every version, interpretation, or extension of your original premise. You may well come up with a better incarnation of your original idea just by doing this. Once you can make a single sentence statement of your game’s premise, go back and check all your mechanics, the theme, rules, the win condition, and components against it. The questions to ask are, “Does this arise necessarily from the premise? Does it only make sense with this premise as its core? Does it strengthen the premise or weaken it?”

- Compare yours with similar games: However original your board game idea is, there’s bound to be another one or several out there that are comparable to it. That’s no bad thing. If your game isn’t functioning as well as you’d like, examine similar games and see if you can uncover their premises. You’ll probably find that even, say, half a dozen similar games all have the same premise—even if one is based in prehistory, another is a futuristic mystery game, and another is an abstract strategy challenge. Then examine the other elements and note how they relate to the premise. Apply what you learn to your own game development.

- A/B play testing: At this stage, you should already have a mockup prototype you can play test. But if you’ve gone through several iterations of play testing the game and you still can’t figure out exactly what’s broken if it isn’t working, then turn to A/B play testing. The A/B just signifies alternate versions based on altering a single variable at a time. Note the most likely areas of the game where you suspect the problem might be and then change one aspect of it. Test it again. Rinse and repeat until you clearly identify what’s wrong and find a fix. Unless you get lucky, this can take a while depending on the complexity of your game. But it’s a methodical and scientific approach likely to bear fruit.

You can’t spend too much time getting your premise right. Once you have a robust, functional premise, you can build out from there by logical steps to add the mechanics, rules, and additional layers of complexity to create a fully realized board game experience. We suggest you adopt “Occam’s razor”—meaning that you try to find the simplest, least complex solution to each step and problem. The law of ‘Occam’s razor” states that the simplest solution is usually the best.

Get the premise right and development is automatic

With board game design, every element—components, mechanics, rules, win conditions, and more—should either strengthen the premise or be necessary for its existence. If something in your game cannot contribute to the premise, it should be reevaluated or removed to maintain the coherence and integrity of the game. If you stick to this principle, you’ll encounter no problems in any other aspect of development. Everything will flow logically forward from that fundamental source.

Let's talk!

As soon as you’re ready to create your final prototype to hawk around the cons and tout to game publishers—or if you’re ready to print your first run of games for your Kickstarter campaign—talk to us. We have decades of experience in the industry. We’re a friendly bunch, too, focusing genuinely on customer care. Get in touch for an informal chat, to find out how we can help you, or to get a competitive and no-obligation quote for your project. We look forward to playing our part in your board game’s success!